Optimising psycho-therapeutic input in an acute inpatient unit. Every interaction a therapeutic interaction.

Keynote to Swedish CAMHS conference, 23 Apri,

2013, Halmstad Sweden by Josephine Stanton.

Note: In preparing this verbal address for the internet I have removed references

to, and photographs of, any living people except myself, Andre, Tania Windelborn,

Johnella Bird and my friend from whom I sought advice. I have also removed

specific reference to my workplace. The views I describe are mine, not those

of the organisation.

Introduction

Thank you for inviting me. It is lovely to be in Sweden. As young New Zealanders in the 70’s we looked to Scandinavia as a kind of model society. I have connected with Swedish people at various important times in my life. So I am enjoying being here.

I feel very humble standing here, speaking in my only language, depending, for any possibility of communication, on the ability of every other person in the room, to speak at least 2 languages. I do tend to talk fast, especially when I get excited, but I will make an effort to stay very calm. I do get excited about this subject, I would appreciate it if I do get too fast if some of you would be able to make a hand signal like this, slow down.

I would like to tell you a bit more about where I come from and how I got to be where I am, outline the importance of every interaction being a therapeutic interaction and describe three strategies; one I call 'bringing out the grains', thinking in circular causality and containing and nurturing staff, including ourselves. I will finish by talking about how I manage my anxiety.

My Story

I come from New Zealand, almost off the edge of the world. You can get maps with NZ in the centre but then Sweden would be almost off the edge.

This is my great, great, great grandmother, Eleanor Stevenson. She was a Quaker woman and came to NZ as a widow leaving her children, including a 4 year old, in England. She made a 4 month journey in a sailing ship to the other side of the world. The European population in New Zealand was probably about 1,000 then with less than 200 of them women. Her children grew up and followed her as adults.

Skipping a couple of generations this is my paternal grandmother, with her husband and my uncle.

This, a more recent photograph, is my maternal grandmother at her 80th birthday party.

These grandmothers represent an aspect of my heritage in which I have great pride. They both went to university which was an unusual thing for women to do in NZ in the early 1900's and it also says something important about the men who married them.

Why I am telling you about this is to let you know that I come from a line of women who stepped outside of the norm. That is what I am aiming to do today. I won't be talking about standard good practices in acute inpatient units. I will be assuming that and focusing on how we push the boundaries.

My history in acute psychiatric units

I began my work in psychiatry in 1984 in adult acute psychiatric units. I was stunned by what I saw. I had expected bad therapy, but not expected no therapy. There was a supremacy of biological psychiatry. We used huge doses of medication. The most chlorpromazine I ever saw anyone have was just over 3 grams. He fitted. In any psychological formulation that happened parent blaming was prominent.

When I heard people from the antipsychiatry consumer movement describing psychiatry as spirit breaking I felt the truth of it and realised I had been part of it.

Returning 13 years later to inpatient work as part of my Child and Adolescent sub-specialisation was a different experience. Biological psychiatry was still important but psychological and systemic factors had a much higher profile. Treatment plans had multi-disciplinary input and were about a lot more than keeping patients safe while their medication worked. Despite all this I still found it extraordinarily challenging.

Over the next few years working in the community I developed a passion for collaborative work, optimising systemic and psychotherapeutic intervention and making my evidence based knowledge and expertise available in a hope inducing rather than a spirit breaking way. I developed this website with a colleague, Tania Windelborn.

In 2007 I returned to inpatient work. I was unable to resist the dual challenge of having another go at a task I had previously been overwhelmed by and trying out my ideas about working collaboratively in an environment where involuntary treatment was an everyday practice.

Therapy in an Acute Inpatient Unit

In my training I was taught that psychotherapy should be a carefully managed process, with identification of suitability for therapy, building rapport and engagement, assessment, formulation and treatment. Six to 12 sessions over as many weeks would be considered brief. This clashes somewhat with the culture in an acute inpatient unit where young people arrive in a context of crisis, often out of hours, often involuntarily, usually experiencing acute psychotic disorganisation or acute suicidality, with an unpredictable period of engagement averaging 10 days.

The issues are similar for group and family therapy. Group therapy was traditionally a major strategy in inpatient care, but this was looking at longer stays. Even the brief adaptations of DBT for adolescent inpatient environments are looking at 2 weeks [1]. The average length of stay is 10 days. it is the young people who would benefit most from those groups who have the shorter stays so even a 2 week programme is not feasible.

Family therapy is a significant need for our population. We spend a lot of time with families, but not doing what is usually thought of as 'family therapy'. We did attempt to schedule dedicated family therapy sessions but they were usually hijacked by the latest crisis, or decisions which needed to be made.

Every interaction a therapeutic interaction

Where to from here. I hope you are guessing that we don't give up. We have limited possibility for scheduled therapy sessions or groups and we need to make the most of them. What we do have plenty of in an inpatient unit, are interactions, with young people, family and community agencies. It is my thesis that it is in these many interactions that the power of an acute inpatient unit lies - for good or for ill. Hence in the title of this talk, 'Every interaction a therapeutic interaction.'

Of course most of these interactions will be with members of the nursing team. The Monday to Friday clinicians are in the unit less than a quarter of the time.

How many of you work in acute inpatient units? How many don't. There are a lot of you. I hate to think of you sitting here for the rest of this hour hoping those who do work in inpatient units are paying attention and wondering what there will be for morning tea. You may be in a work environment where you are more able to engage in planned, dedicated therapy sessions. But, whatever your work environment this will never be all of the interactions. You don't have so many interactions in community work. But the issues are the same. So, keep an open mind, there might be something of use for you between now and morning tea.

That was the introduction. Now I am going to focus on three intersecting and overlapping strategies:

- Bringing out the grains.

- Thinking in terms of circular causality

- Containing and nurturing staff, including ourselves

These are not all there is but I think they are about as much as we can cope with today.

Bringing out the grains

My training in psychiatric interviewing, starting in the 80's, was done in a psycho-dynamic context. The purpose of a question was to get information into my mind so that I could identify deficits and develop a formulation and treatment plan. I learnt the value of empathic comments, interpretations and formulating patients' problems for them so they would have a therapeutic experience. I wanted them to realize I how keenly perceptive I was and how much I had to offer so they would become engaged in treatment [2]. The focus was on my knowledge and skills.

When I did some workshops with Johnella Bird I realised that something different was possible. I don't know if anyone has heard of Johnella?

She is a New Zealander and developed her work out of narrative therapy [3, 4]. She has done some teaching in Sweden. Her work is particularly helpful in making every interaction a therapeutic interaction as it addresses the detail of conversation in the context of a big picture in a way which can be applied to any interaction. She has helped us in a number of ways in the unit. Tania Windelborn and I were so inspired by her approach that we developed this website I showed you.

This Arabian saying expresses something central to the shift Johnella's work enabled me to make.

A friend is one to whom one may pour out all the contents of one's heart, chaff and grain together, knowing that the gentlest of hands will take and sift it, keep what is worth keeping and with a breath of kindness blow the rest away.

Sometimes we cannot see the grains for the chaff and it can seem as if we need deep shaft mining rather than gentle hands and a breath of kindness to identify the grains. The tools we have to bring out the grains are careful listening, carefully worded questions and a carefully worded reflections and summaries. A grain can take all sorts of forms.

A grain may be an intention supporting an action. For example, with a parent who is lecturing a child, you can see this is not helpful. You might ask, 'What are you hoping Johnny will learn from that?' to bring out the intention.

A grain may be a value a person holds. An example is a child who is constantly coming up against teachers over how they apply the school rules. You might ask, 'Is fairness important to you?' to bring out this value.

A grain can be a sense of agency someone could experience. For example, with a person who is engaging in self numbing behaviours such as substance abuse, you might ask, 'Are you trying different things to find a way to live with these horrible feelings you have been experiencing?' which places the person as actively engaging in sorting out their life.

Any of these you can then follow up with 'How well is this working for you?'

The purpose of these questions is shift in the person’s mind, towards movement, towards getting more in touch with aspects of themselves they value and respect.

I'd like you to do some thinking about how we ask questions. I want you to think of two contexts for asking a colleague about a clinical decision which surprised you. The first is with a junior colleague about whose work you have had concern for some time. 'What sort of things were you thinking about when you decided to do that?' You are asking in order to identify deficits you can address. The second is a senior colleague whose work you admire. 'What sort of things were you thinking about when you decided to do that?' You are asking because you are hoping you might identify 'grains' from which you can learn something.

In a similar vein, I have a friend whose children are all a bit older than mine. At times I would ask her about what she did, perhaps about pocket money or getting the children to help with the dishes. I was asking, looking for 'grains' because I was hoping I would learn something I could use in my life. This is so different from the way I asked questions of the parents I met at work.

I wouldn't know how to live the lives of many of the people I am attempting to be useful to at work. I thought I was stressed when I had 3 preschoolers. I had a husband who didn't hit me. I had secure housing. I was able to buy groceries and my children didn't have major health needs. The people we work with need all sorts of resources to enable them to live their lives. We probably won't find them if we don't look actively and if we look actively we will often be surprised.

Preparing this talk has functioned in this way for me. As I have gone through the process of figuring out what to say today a lot has happened in my mind. I have become a lot clearer about what I do do and what I need to do better. So, I am certainly getting something out of this process. I hope you are too.

Video clips

I would like to show a couple of clips of Johnella's work. These are both role plays. I am really sorry about the sound of the first one. I hope you can hear it. It is of Johnella interviewing Andre in the role of Marvin, a psychotic teenager who has grandiose delusions that he is running for president of the United States. You will hear him talk about 'the campaign' and 'campaigning'. For those of you who know Andre you will realise he has missed his opportunity for a Hollywood career.

Grains are not obvious here. Notice how alert Johnella is to looking for possibilities of where she might find grains.

What do people notice?I have highlighted a few things here.

M: Just that I'm pretty busy so I’m not sure how long I can stay today. I’ve got lots of things to do. Obviously President - campaigning.

J: You’re a busy sort of guy.

She has highlighted a description of himself he might value, in a sense straight forward reflection but there are a lot of other possible choices.

Being made up of the right stuff and having the right connections and it's meant to be. Obama could do it, I can do it. It’s an underdog thing. He was an American. I am. It’ll be great. Schwarzenegger.

In response to all this thought disordered stuff she focuses on the idea of 'underdog'. There is potential here for identifying a value or a direction. Notice the persistence she shows around this idea of unrecognised potential.

M: It’s like the unrecognised potential that's quite nice. Me being here.

J: Are you somebody that for a long time that the potential you have has ...

….. He talks over her

J: When you think back to when you were little was the potential recognised then?

J: Yeah. It’s always been unrecognised.

J: Do you think your Mum recognised any potential?

Notice the persistence she shows round this idea of unrecognised potential, looking to place it in a time context and the possibility of grounding it with his mother.

This was all totally unrehearsed, she had no idea what we were going to say.

The second clip is of Johnella interviewing me in the role of Susan, a mother who, in her desperation, is putting down Tania (from the website) in the role of Maggie, her daughter.

There is plenty of chaff in this one she has to work really hard to get through it.

What do you notice?

The reason I wanted you to look at this is to indicate that it is not just about being 'client-centred' and following the person's lead. Sometimes we have to take control, work hard and be persistent to keep the focus on the grains. Let's have a look at this.

Susan, could you just pause for a second. I know, clearly there’s heaps of things you need me to know,

She takes control of Susan's behaviour, while also validating the intention which supports the behaviour, for Johnella to have the information she needs to help Maggie.

Look at this one

S: Well, answer her.

J: It’s okay, it’s all right. I’m okay. We are just getting to know each other a little bit.

….. Susan does more of the critical, attacking talk towards Maggie

J: Okay. I’m feeling okay right this minute, I’m pleased, ... the fact that you’re trying to make this better for me I really appreciate, but it’s okay at the moment.

Johnella takes the subtle grain of the part of the intention Susan holds which they can both value and makes it explicit.

Would you like to look at it again?

I can’t use this approach with a fraction of the skill Johnella has, but even though I am not particularly good at identifying grains, I have found that it has made a huge difference to my work to be sitting with a person thinking, 'what can we discover in this conversation about the resources you have that are of use to you in your life?'

On tap not on top

It's not just about their knowledge. We have responsibility to make the knowledge and skills we hold available in the service of the people we are trying to be useful to, on tap, not on top. I tell young people that my job is to help young people to get their lives going as well as they possibly can. This is their lives according to their values.

Expertosis

Before I move on I want to give a warning about Expertosis. It is not a proper English word, but does appear on the internet. You may have a Swedish word for it. It is something we all suffer from at times.

'Expertosis develops when we believe our knowledge is the only knowledge or the best knowledge and impose it on others. It is particularly common among professionals … none of us is immune' [5]

There is a certain irony in my standing here talking about this giving you a lecture. Expertosis can be undermining for families but it is at its most risky with other staff. As the expertosis sufferer talks with great confidence about the insightful, effective work they are doing other staff members hear this and question their own competence, thinking, 'how could I ever be as good as they are?' They may withdraw from offering their own therapeutic input, believing it to be inferior to that of the expertosis sufferer when that is usually not true.

I don't know whether you are seeing a bassoon player or a beautiful young woman. It is a reminder that there is always more than one way to see things.

Circular causality

Linear causality describes the ordinary, everyday thinking that we do. An event at time one is understood as the cause for an event at time two. To understand an event we are looking for information about what went before, what is behind the current event. If there is dysfunction there must be pathology causing it. This means that if we are to be useful to the people we serve we need to figure out what the underlying pathology is and work out a way to fix it. 'Identify the tumour and cut it out'.

Circular causality supports the idea of a 'vicious cycle' or 'victorious cycle'. Co-existing events, none of which is particularly significant in itself, can be understood to affect and amplify each other. With the financial markets a small increase in business confidence leads to more investment in the stock markets which leads to a further increase in business confidence which can increase exponentially until the bubble bursts and it all moves in the opposite direction.

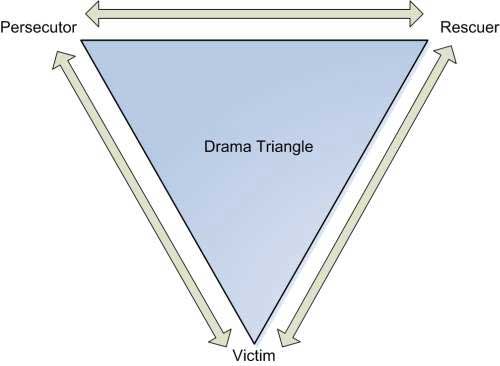

We are all familiar with the vicious cycle in the victim, rescuer, persecutor triangle.

If you take up a rescuer role with someone in the victim role and let them know you will make them feel better they are likely to slip more deeply into the victim role. In frustration you might move into the persecutor role, in anger at their not responding to all your care, etc.

A vicious cycle is proposed in OCD, where performing the ritual is strengthened by the reinforcement of lessening of anxiety when the ritual is performed. Similarly in Bulimia Nervosa, bingeing and vomiting are followed by feelings of self disgust which lead to restricting which lead to overwhelming hunger which lead to bingeing and the cycle self perpetuates. Depression can be understood similarly, with poor sleep and poor energy levels meaning the person is less likely to engage in activities which lift mood. Guilty thoughts exacerbate low mood etc.

Thinking this way means that small shifts can make a significant difference. Big problems do not necessarily indicate severe underlying pathology.

In OCD we leave alone the most disabling rituals initially and engage the person in response prevention of the lowest ritual on their hierarchy, in Bulimia Nervosa we don't try to stop the bingeing and purging but get people to record their thoughts, emotions etc. and target the restricting, engaging the person in eating regular modest meals to reduce the intensity of the hunger. There are many small interventions shown to have an effect in depression, exercise, activity scheduling, bibliotherapy etc. A recent meta-analysis showed that low intensity interventions are just as effective in severe depression as mild depression [6].

The idea that small changes can make a difference can be hope inducing for young people and families as well as clinicians.

Small interventions can interrupt a cycle; e.g. a no chase policy to absconding or matter of fact response to cutting remove emotional intensity which might reinforce these behaviours. Another example is engaging a young man with negative symptoms of psychosis in a game of volley ball or a cooking group. This can help interrupt a cycle whereby he becomes increasingly withdrawn, increasingly socially phobic and increasingly disinterested in getting well and engaging in life.

A conversation bringing out grains can have ongoing small effects. This can be particularly significant with disempowered, disconnected parents feeling blamed and stigmatised as a result of their child's illness. If they are feeling they are not able to help their child they may hang back, which means they are not able to help their child, but if they are able to engage more fully as their confidence builds this can break a negative cycle.

Once you are working in this way of thinking of the possibilities of small interventions there are a wide range of therapeutic interventions which can be supported by a range of staff.

SPARX is a computer game teaching CBT skills.

It was developed in NZ shown in an RCT to be effective in mild depression [7]. It has six levels, each taking about 20 minutes which can be done independently of staff intervention.

All the interactions on an inpatient unit provide a wealth of opportunities for supporting learning of mentalizing. Other options include engaging in social activities, teaching of mindfulness and other emotion and mood management skills, making some progress with education etc.

Exploring sensory strategies is ideally suited to inpatient care, developing a sensory box, trying a weighted blanket, hand massage etc.

This is a weighted dog which some people find helpful in getting through distress.

This is me with my work props I carry round with me.

The iPad has the Psychfeedback app shown on our poster.

The 'How am I?' questionnaire enables the young person to self rate and 'this conversation' questionnaire enables them to give feedback on the conversation they just had with you. I also find the 3D brain a particularly useful app.

In my briefcase I have toys with interest or sensory properties for young people to fiddle with and various other paper resources. These are cards. The ones I use most are those with feeling words and pictures, here are some examples.

These cards are available from St Luke’s Innovative Resources - www.innovativeresources.org

I use them by inviting the young person to look through and identify any feelings they are experiencing.

None of this will change any of these young people's lives, but it may help get a bit more understanding or even with the openness they have to clinicians they meet in the future. It is also modelling, from the clinical leader of the unit, the importance of consideration of the young person, and working hard to bring their voice forward in every interaction.

Over the years we have had a number of young people engaging in high risk behaviours which have been resistant to a wide range of interventions. We have had to balance, on one hand, the desire to try to protect them by using a locked environment and a watch and, on the other hand, with the harm that an approach like this can do. Apart from the fact that even this sort of coercive care does not guarantee safety, looking at some of these young people locked up has reminded me of an albatross in a cage, truly spirit breaking. We have avoided taking this route, tolerated the risk and been available for them to have a space in the open unit in a locked area for brief periods in a way which enables them to move their lives forward.

It is only a piece of the puzzle but removing the anxiety in intense responses has been part of breaking the cycle which has enabled the young person to develop and mature and move on to a life worth living. In many of these situations there has not been significant pathology either in their personality structure, or family relationships once they have been able to get out of the vicious cycle.

Containing and nurturing staff (including ourselves)

Please would you look at this slide and consider this quotation. I'll read it.

To effectively switch from defensive to social engagement strategies, the mammalian nervous system needs to perform two important adaptive tasks: 1 - assess risk, and 2 - if the environment is perceived as safe, inhibit the more primitive limbic structures that control fight, flight, or freeze behaviours [8].

This has important implications for an acute inpatient unit. There are so many ways you can feel unsafe in an acute inpatient unit and we need the staff team to be in social relating, not defensive mode.

Defensive practice has a high risk of being spirit breaking. It is always easier to justify more paternalistic, restrictive, biological practice in an inquiry than more collaborative, psychological, less restrictive practice. Occasionally I end up saying to a young person who tells me they may kill themselves if they leave hospital that hospital is not helping and that is a risk we need to take. I will never know if there are lives I may have saved by enabling a young person to find more adaptive ways of coping. But if one completes suicide I will be very vulnerable. Similarly with the young people with ongoing risky behaviours I spoke about. If one of these had left the unit and been raped or murdered on the street or killed themselves we would have suffered under public scrutiny. It would be much easier to have justify suicide if we had kept them locked in the HDU.

If members of the nursing team move into defensive practice there is a risk of a vicious cycle where patients who feel less connected to staff will be more defensive themselves and less able to engage with what the nurses are offering which increases the risk of use of 'power over' strategies such as seclusion and restraint. This has an associated risk of increased staff assault and abuse leading to increased staff defensiveness. Use of collaborative problem solving has been associated with reduction of use of seclusion and restraint in youth inpatient units [9, 10[. To engage a young person in collaborative problem solving you need to be in a social relating, not a defensive mode.

Leadership is crucial in containment of staff. It is working in this context that I have come to understand the meaning of true consensus. What it means is that in a decision making process it is not about seeking agreement from each member but seeking differing views and working, before bringing the views together, to be identifying the 'grains' which support each differing view, in order to enrich the decision process. So if I am wanting to vary a protocol and one of the others in the leadership team disagrees my first assumption is that they have thought of something I haven’t and I need to understand what that is. This can be slow, but in a system like an acute inpatient unit change is high risk and this process provides a depth of containment. A corollary of this is that the team will stand by any member who makes a decision in a hurry, with review afterwards.

The leadership group needs to be visibly attending to staff safety, eg multidisciplinary risk assessment and safety planning, identifying potential triggers and problem solving around them, staff training in de-escalation and adequate staffing levels. We need to take any assault seriously and have zero tolerance for verbal abuse. We also need adequate antipsychotic doses of medication. Involuntary treatment in an acute inpatient unit is not the context to start low and go slow. There also needs to be meaningful nursing input into medication decisions. We need to be acknowledging and supporting work towards connection. Having family members stay on the unit can be helpful. It is not totally straightforward, we had one patient’s brother assault another patient once, but that is the exception.

The nurturing I am talking about is about promoting a sense of confidence and competence in staff as therapeutic agents. Actively looking for 'grains' in the talk and practice of all staff is important. As in the example with Johnella managing Susan's behaviour in the video clip, it is containing for the staff to know that they will be supported in what they do but will get feedback and control can also be taken by clinical leaders. This commitment to identifying 'grains' needs to be part of conversations with and about young people, family members, staff in the unit, students, referrers and anyone else.

Thinking in terms of circular causality supports this sort of nurturing because it means that each interaction and small intervention any member of the staff team engages in is of potential important therapeutic value. Any clinical intervention needs to be multi-perspective; the young person, the family, the outpatient team and the whole staff team on the unit. Interactions happening in all these contexts can be important.

I have created an example of a fictitious, but typical young person, to illustrate a fictitious, but typical, illustration of including the nursing team in a clinical intervention on a Friday afternoon. This is of a young woman with emotional dyscontrol admitted following a suicide attempt. She had refused to engage in outpatient therapy but in conversation with me she had expressed some openness to considering what therapy might have to offer. I brought her nurse into the room with us and told her about some of the things we had covered in our conversation. These included the care this young woman took to avoid trying new things because of the risk of disappointment and her experience of people not understanding. She had expressed a little bit of openness towards hearing about what therapy might have to offer. I asked the nurse if she, and the nurses over the weekend, could introduce some ideas about emotion management skills. This would not be actual therapy, but a taster. We had talked about how people like us have lots of different ideas, some are helpful for some people and some for others. Meeting with and hearing about a range of ideas from different nurses over the weekend might give her an opportunity to identify different ideas or styles of talking she found more or less inviting than others.

The leadership team needs to be visibly supporting ongoing training and development of skills and supervision and structured reflective practice like the Assisted Interview Role Play Andre and I are presenting in our workshop tomorrow. Time needs to be protected for these activities, especially when the unit is at its most busy because this is when we are at most risk of moving out of social connecting into defensive mode.

Managing the anxiety I experience

For the leadership team to manage the anxiety we experience is crucial to the containment of the unit so I thought I would finish by talking about how I manage the anxiety I experience.

- The first thing is that I retain the awareness of just how important it is for everyone in the unit that I manage this anxiety effectively. It is an important part of my job and I need to give it energy and time.

- Mindfulness is important, stilling the anxiety and connecting with what is generating it and considering the different factors. This is a process which I do partly alone and partly with trusted colleagues. It is supported by my learning over years how anxiety can impair my therapeutic effectiveness.

- I need to make this anxiety and the reasons we need to sit with it explicit. This often comes up with suicidal young people, the need they have to engage with life in order to move forward. Similarly with young people who are disorganised with acute psychotic illness, there is a reduction of risk in having them closely watched in hospital, but having meaningful connections with their family can be healing in important ways and maintain hope. I need to make sure that I make clear to the young person and family the understanding I have about the potential risks and benefits of both approaches.

- Engaging family and young people in the decision process. This can require working hard to find something we can agree on. This comes up when a young person experiencing suicidal thoughts develops a level of comfort in the open unit and is reluctant to leave. They and their family share concern they will kill themselves if they leave. We may be concerned that the usefulness of hospital is declining and the young person is at risk of developing a patient lifestyle with ongoing, escalating risks. We can make alternatives. For example we could offer a brief tightly observed admission to the locked area under the MHA to support safety with the alternative of discharge and regular voluntary open unit respite admissions.

- Consulting with colleagues is important, including clinicians who are working with the young person, other members of the leadership team in the unit, and other colleagues.

- I always see the young person, and often the family, myself if there are decisions being made which could generate anxiety, I do not take over their care, but am not prepared to be part of a difficult decision about a child or young person I haven't met. I am happy to consult to a case, but not to take decision making responsibility.

- Structured experiential reflective practice, like the method we are showing tomorrow, helps me process emotions, access my intuitive knowledge and open up possibilities.

- I need to keep connecting with the values and intentions which inspire my work, the importance of everyone having a chance to live their lives their way and my knowledge of the risk of the spirit breaking effect of defensive practice.

- I also need to keep nurturing of myself as a therapeutic agent by quality supervision, ongoing learning, and keeping up to date with the evidence, eg getting BMJ evidence updates so I know there is nothing major I miss. If people don't know about those they are really worth getting on to.

- I need to know I am doing the best I can in the circumstances. This will not be the best anyone could have done, and may not be the best I could do if circumstances were different, but I need to know I am doing the best I can on the day.

- Last, but by no means least, I pray, connect with the people I Iove and who love me and enjoy my life to the full.

Thank you.

References

- Katz LY, Cox BJ, Gunasekara S, Miller AL. Feasibility of dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal adolescent inpatients. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. [Clinical Trial Controlled Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2004 Mar;43(3):276-82.

- Shea SC. Psychiatric Interviewing:The Art of Understanding. A Practical Guide for Psychologists, Counsellors, Social Workers, Nurses and Other Mental Health Professionals. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998.

- Bird J. The Heart's Narrative-Therapy and Navigating Life's Contradictions: Edge Press; 2000.

- Bird J. Talk that Sings: Therapy in a new Linguistic Key. Auckland: Edge Press; 2004.

- Smart R. Expertosis: Is it catching? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. [Empirical Study]. 1994 Mar;15(1):1-9.

- Bower P, Kontopantelis E, Sutton A, Kendrick T, Richards DA, Gilbody S, et al. Influence of initial severity of depression on effectiveness of low intensity interventions: meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. [Meta-Analysis Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2013;346:f540.

- Merry SN, Stasiak K, Shepherd M, Frampton C, Fleming T, Lucassen MF. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised self help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ. [Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2012;344:e2598.

- Porges SW. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication and Self-regulation. New York, NY: Norton; 2011.

- Martin A, Krieg H, Esposito F, Stubbe D, Cardona L. Reduction of restraint and seclusion through collaborative problem solving: a five-year prospective inpatient study. Psychiatr Serv. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. 2008 Dec;59(12):1406-12.

- Greene RW, Ablon JS, Hassuk B, Regan KM, Martin A. Innovations: child & adolescent psychiatry: use of collaborative problem solving to reduce seclusion and restraint in child and adolescent inpatient units.[Erratum appears in Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Aug;58(8):1040 Note: Hassuk, Bruce [added]; Regan, Kathleen M [added]]. Psychiatr Serv. 2006 May;57(5):610-2.